Sustainability and circular economy themes were prominent at ITMA in early June, at every stage of the manufacturing, dyeing, printing and finishing process. Michael Walker looks at how these play out in the digital textile printing space.

The textile industry needs to clean up its act. If one message was clear from the industry’s first global gathering since 2019, it is that the sector is coming under pressure from a variety of directions, ranging from tightening environmental legislation in Western markets – the EU in particular – and rising consumer expectations of brands to the desire to make the ‘right’ choices.

This was reflected in statements made at the event’s opening press conference by ITMA Services’ board member Regina Bruckner, saying that one aim of the show was to inspire the industry to ‘modernise and future-proof’ itself, while Ernesto Maurer, president of Cematex, admitted that, ‘Sustainability in manufacturing and processing of textiles has become more important than we thought in the last four years,’ adding, ‘We can either drive the change or be driven by it.’

Mr Maurer also noted that part of this involves ‘being present with those making legislation’ to help ensure that it is ‘reasonable, doable and feasible’.

Away from the politics, manufacturers who serve the digital textile printing sector are responding in a variety of ways. Although digital print has an inherent advantage in flexibility in response to short lead times and reduced run lengths and thus less wastage of materials, transport and storage with their related emissions, there is still room for improvement within the various printing technologies.

Water, water everywhere

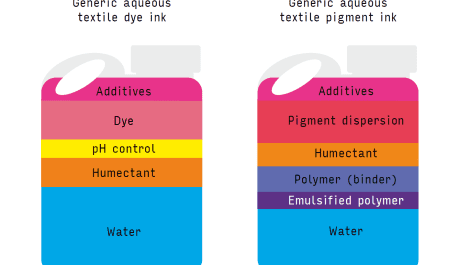

A key area is the use of water, which in some types of digital print isn’t much different to analogue alternatives in terms of pre- and post-washing or steaming. What’s clear is that, however colours are applied to fabrics, it generally uses a great deal of water, so it’s not surprising that ink types that dramatically reduce or sometimes completely do away with wet processing are the focus of sustained development efforts.

Ever one for bold headline-making claims, Kornit Digital’s CEO Ronen Samuel announced a commitment that the company’s technologies would be enabling the decoration of 2.5 billion apparel items by 2026, saving 4.3 trillion litres of water and 17.2 billion kilograms of equivalent CO2 emissions compared to conventional techniques.

Kornit’s Apollo high-volume DtG printer automates for efficiency

Kornit’s Max technology is set to play an important part in this, cutting both water and energy usage, according to chief product officer Danny Gazit; energy usage in the drying/curing stage is further optimised by the company’s Smart Curing technology, which appears with the new Apollo industrial-strength DtG system, as well as the Atlas Max Plus and Atlas Max Poly units.

Sustainable objectives are enshrined in the very name of Kyocera’s unexpected entry into the sector, with the Forearth printer. Noting that the analogue to digital transition had progressed more slowly than anticipated, the company’s Tayo Hamano, senior general manager of the Corporate Management Promotion Group, said that the development of pigment inks that require no post-print washing was key but that the hand-feel of pigment-printed fabrics was inferior to that of those printed with other ink types. ‘If this is solved, the significance of digital textile printing would be enhanced and the transition would accelerate,’ he stated.

Kyocera’s attempt to do just that draws on the company’s experience in inks and printheads – Mr Hamano said that Kyocera printheads are the market leader in textile applications, measured in terms of square metres printed – and involved the design of a new recirculating inkjet head for the new printer, which uses 16 of them and supports up to eight colour channels.

Sho Taniguchi, general manager, Industrial Printing Business Development Division explained in more detail how the combination of the Kyocera Integrated Print System (Kips) and ‘Picfy’ inks enables pre-treatment, colourants and post-treatment solutions to all be jetted in one pass, cutting water consumption from 135l/kg of printed fabric via dye-based methods to just 0.02l/kg.

The inks have been developed for both hand softness – which Mr Taniguchi described as ‘unbelievable’ – and wash/wear durability. The Forearth system, which is also quite compact at 4.6 x 2 x 2m and is expected to be available in autumn 2023, can print on just about all fabrics, from cotton and rayon to polyester and blends, silk and nylon. Mr Taniguchi noted that although the pigment inks are more expensive than dye alternatives, he anticipated that total production costs would be similar.

Mimaki suggested that digital processes can use as much as 95% less water than analogue ones but also noted that its current estimate for the penetration of digital textile print was around 7.8% in 2022. However, this is expected to grow to some 20% by 2030, so that switch alone could potentially save a lot of water. The introduction of its 550sqm/hr ‘usable quality’ Tiger600-1800TS printer may help drive that growth.

Mimaki’s take on further water reduction goes via transfer printing, which it says makes the printer and its operation simpler, rather than the direct-to-fabric approaches adopted by many others. Using an adapted TS330-1600 roll printer and a new paper called Texcol from Dutch manufacturer Coldenhove Papier, waterless pigment-based transfer printing is possible. According to Ramon Overdijk, marketing and sales director at Coldenhove, the process transfers an entire coating, not just the ink that is jetted onto the paper and this makes pre- and post-treatment redundant. The technology also reduces the amount of ink required to achieve sufficient density and saturation, according to Mr Overdijk.

A whiter shade of pale

Mimaki also introduced a different slant on recycling, with general manager of global marketing Yuji Ikeda pointing out that of some 92 million tonnes of polyester produced annually, only around 1 million is from recycled sources, and most of that is from PET bottles and not polyester fabrics. To tackle this, Mimaki is developing a process called Neo Chromato that effectively undoes dye sublimation printing, removing the colourants from polyester fibres in a process that apparently allows re-use of the fabric up to 20 times.

Describing this as a ‘first step’, Mr Ikeda said that the process was probably a year from commercialisation but involved using an ‘absorber’. He acknowledged that establishing a functioning route to collect used dye-sublimated polyester fabrics will also be part of the challenge and that educating brand owners would be a key part of that. He could not comment on the cost of the process as the system is not yet finalised, but it does sound like a genuine step towards a circular re-use of polyester rather than the usual downward spiral of processing into products of ever lower quality and value.

Konica Minolta showed samples produced with the Virobe pigment ink

Konica Minolta is another player that is looking into the development of pigment-based inks that will reduce the post-processing in its industrial textile printing machines. Its concept is called Virabe, and samples were shown on its stand at ITMA. DuPont has also announced an intention to focus on pigment ink development, both in DtF and in other textile applications.

Aleph has integrated ‘printed’ pre-treatment into its LaForte 400H printer, jetting the solution only where ink is to be applied. The company debuted a new pigment ink at ITMA, which CEO Alessandro Manes said has a new molecular structure and provides results that are very soft to the touch. In this productivity sector, SPGprints is also adding a pigment ink option for its Jasmine 1.8m direct-to-fabric printer, initially shown at ITM 2022 in Turkey with acid and reactive ink options.

EFI Reggiani claims water reductions of up to 95%, 75% for chemistry consumption and 60% for power for its EcoTerra line, which integrate pre- and post-treatment into the one unit, also saving space, backed by the ability to generate carbon footprint, water consumption and other sustainability information for brand customer reassurance via the newly announced Query software.

It seems that the industry has heard the call loud and clear and is moving to address environmental issues – at least in the production of fabrics and garments, if not so much their end-of-life disposal – with some alacrity. The inherently less wasteful production model of digital print, in which material or garments ideally aren’t even produced until they’ve been sold, coupled with these further refinements, not least the charge for pigment, shows that while there may be some way to go, we’re off to a good start.